Researchers from Peking University have developed an on-chip microcomb that bridges the frequency gap, enabling seamless synchronization without computationally demanding processing.

Optoelectronics combine optical components, which use light, with electronics, which rely on electrical current. These systems have the potential to transmit data faster than conventional electronics, making them promising for high-speed communication technologies. However, their deployment has been limited due to difficulties in synchronizing optically generated signals with traditional electronic clocks. This challenge arises because optical and electronic components typically operate at vastly different frequencies.

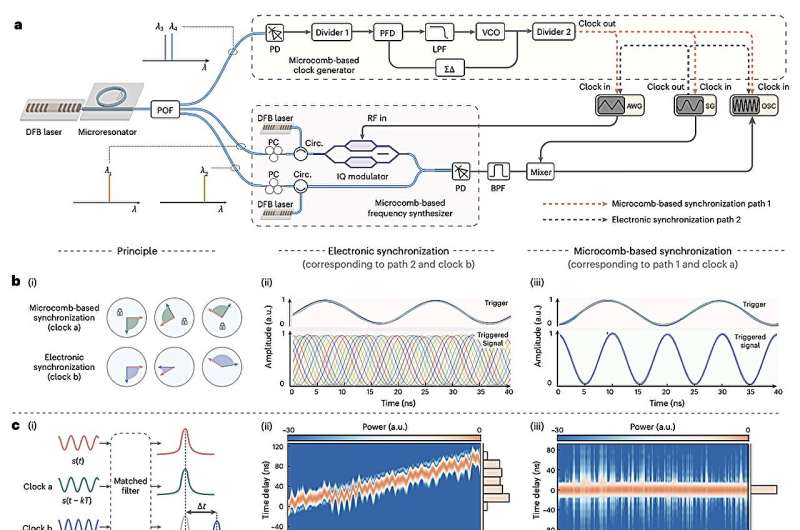

Optical signals generally function at hundreds of gigahertz, whereas electronic circuits operate at much lower frequencies, typically in the megahertz to gigahertz range. This frequency mismatch hinders synchronization, affecting the reliability and efficiency of optoelectronic systems. To address this issue, researchers from Peking University, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and other institutions have developed an innovative on-chip microcomb—an optical device that generates a precise series of equally spaced frequencies across different wavelengths. Their findings suggest that this microcomb could act as a clock for both optical and electronic components, synchronizing signals across a wide frequency range.

“Optoelectronics could enable fast and wideband information systems,” wrote Xiangpeng Zhang, Xuguang Zhang, and their colleagues. “However, the large frequency mismatch between optically synthesized signals and electronic clocks complicates synchronization.” They describe an on-chip microcomb capable of synthesizing single-frequency and wideband signals, spanning from megahertz to hundreds of gigahertz, providing a stable reference for electronic components.

Unlike previous synchronization approaches, this microcomb does not require coherent digital signal processing—a computationally demanding method used to correct frequency mismatches in software. Instead, their synchronization strategy aligns optically synthesized signals and electronics with high precision, enabling efficient data transmission without heavy computational costs.

To demonstrate the microcomb’s potential, the researchers developed an optoelectronic wireless device for both sensing and communications. In this system, the microcomb acted as a transmitter, enhancing data transmission and remote sensing capabilities. Future improvements, such as integrating photodetectors with larger bandwidths, could extend the microcomb’s frequency range to cover the entire microwave and terahertz spectrum. Additionally, its high repetition rates and low power consumption make it an attractive solution for widespread optoelectronic applications, paving the way for next-generation communication systems.